Jonathan Choti, an African-born scholar and Assistant Professor of African Languages and Cultures at Michigan State University, will engage with counterparts in Kenya this summer as part of the 2022 Carnegie African Diaspora Fellowship Program.

Choti, who is a faculty member in MSU’s Department of Linguistics, Languages, and Cultures, received the prestigious fellowship to co-develop and strengthen curriculum, grow research, and mentor graduate students in the Swahili Program at the University of Kabianga (UoK) in Kenya.

The Carnegie Scholar Fellowship Program supports educational projects at African higher education institutions and is designed for African-born scholars based in North America. Choti joins a roster of 527 scholars who have received the fellowship since the program’s inception in 2013.

“I feel proud to be a recipient of this prestigious award and to know that hard work, determination, and grit can bear fruit,” Choti said. “It’s a confirmation that my work is valuable and fulfilling and a confirmation of my goal to be better every day so I can best help my students.”

“I feel proud to be a recipient of this prestigious award and to know that hard work, determination, and grit can bear fruit.”

Choti said he applied for the fellowship because of the opportunity it provided to share his American experience and education in his home country. He also is excited by the possibility of fostering cross-cultural exchanges between MSU and UoK.

“Our educational systems are so different,” he said. “I want to give back and enrich educational programs in Kenya and contribute to their growth. It feels really great to realize I’ll be there sharing knowledge, experience, and skills, and being a role model and motivator of young people.”

Surmounting Barriers

Choti grew up in a close-knit extended family in southwest Kenya in Nyangusu, a rural settlement near Lake Victoria in Kisii County. His father had two wives and 16 children. Choti was one of eight from his biological mother. His stepmother had eight children as well. By the time he was 10, one of Choti’s brothers and his father had died.

Choti’s mother practiced subsistence farming and provided food for the family through their small farm. Getting to school was a challenge because the family had meager resources. Choti attended a village school near home from first through fourth grade, then went to live with an uncle through seventh grade. When he finished his primary education, the family didn’t have enough money to send him to high school, so he repeated seventh grade for three years.

“I was bored learning the same stuff for three years,” he said. “I liked sports. I liked making friends. But I wanted to be like my older brother Charles Otoigo. He was very smart and the pace setter. He would bring books for me to read and helped me develop learning skills.”

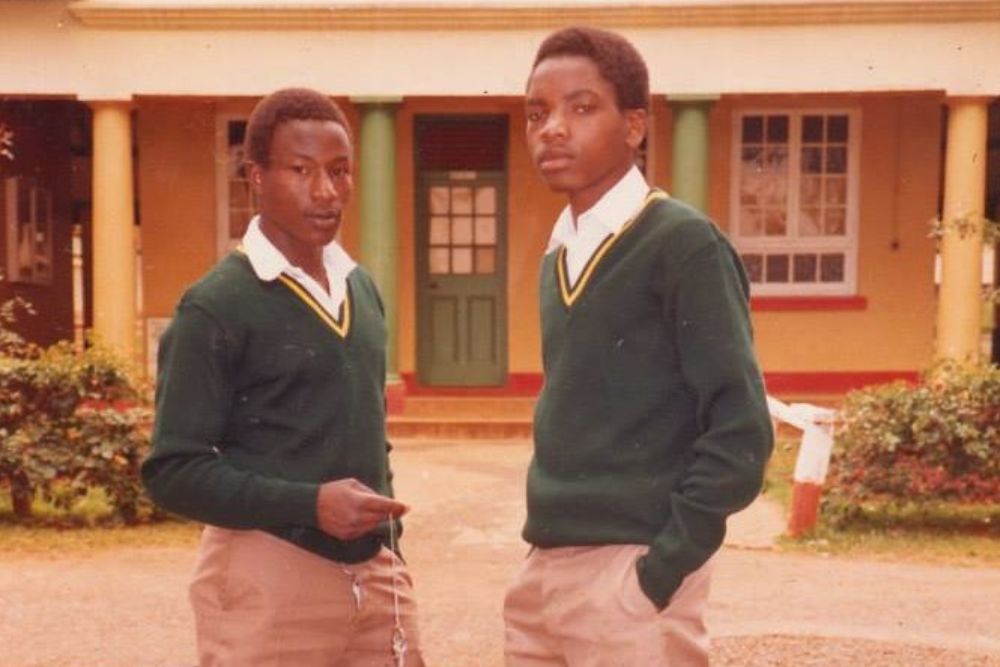

Choti attended Kisii High School for six years. He confided with his high school principal, Joseph I. Kinyua, about his family’s situation. The principal listened and found a way for Choti to receive an annual government scholarship to attend high school. The community, too, pulled together with his family to raise additional funds. He completed four years of secondary school and two of high school and excelled, setting his sights on attending a state university to study linguistics, languages, and cultures. He pursued a BA with a double major in Swahili and English Linguistics and a minor in Sociology at Egerton University where he also completed his MA in English Language and Linguistics through a government scholarship.

Although his natural ability for languages shaped his educational interests and path, Choti was unsure where his studies would lead. Until then, his teachers had been supportive. But at the university, he encountered his first less-than-positive experience with an educator.

“I decided right then that I wanted to be a professor of linguistics so I could encourage people to study the subject, not scare them away,” he said. “It was my goal to set the standard for being an empathetic teacher. That professor never knew his negative manner motivated me to be who I am today.”

Called to Teach

Choti first came to MSU to pursue his Ph.D. in Linguistics after earning his master’s and bachelor’s degrees from Egerton University in Kenya. He currently teaches Swahili language and courses on African cultures, languages, and literature. Most summers, he leads a six-week study abroad program in Tanzania.

“We from Africa who came and obtained higher education degrees in the United States have a role to play in connecting our two regions so we can enhance research and understanding.”

Considered a model teacher and scholar, Choti has received numerous awards and fellowships from MSU, including the Lily Fellowship, the Excellence Award in Interdisciplinary Scholarship, and the Mid-Michigan Spartans Quality in Undergraduate Teaching Award. Some of his motivation to excel, he said, is innate. Other motivation is more external, emanating from the leadership and supportive environment of his department. But by far, he says, his greatest reward and inspiration is the opportunity to teach, motivate, and see his students succeed.

“I have very good experiences with my students every day,” he said. “I am honored to say that teaching is my calling and profession. This is my job and what I want to do in life. It always has been.”

Giving Back

Choti’s two-month fellowship at the UoK commences at the end of June and will last through August. During that time, he will collaborate with his host Dr. Mohammed Ramadhan Karama in the Department of Languages, Linguistics, and Communications at UoK to build and strengthen programs at the relatively new institution that became a full-fledged university in 2013. The project also will establish linkages between UoK and MSU for student, scholarly, and research exchanges in the area of languages and linguistics.

For Choti, the fellowship represents the chance to create opportunities for students and scholars that were unavailable during his college years in Kenya. His ultimate goal is to connect institutions, foster exchanges, and encourage globalization so no student is left behind.

“We from Africa who came and obtained higher education degrees in the United States have a role to play in connecting our two regions so we can enhance research and understanding,” Choti said. “When we begin to share our common issues, when we start to understand each other’s cultures, we begin to see that diversity is part of our existence and can lead to peace.”